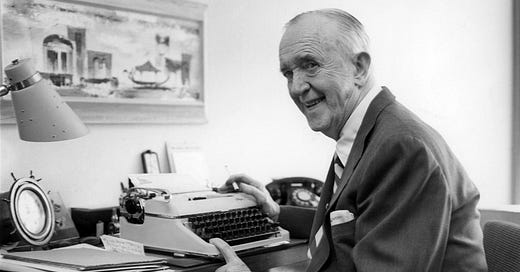

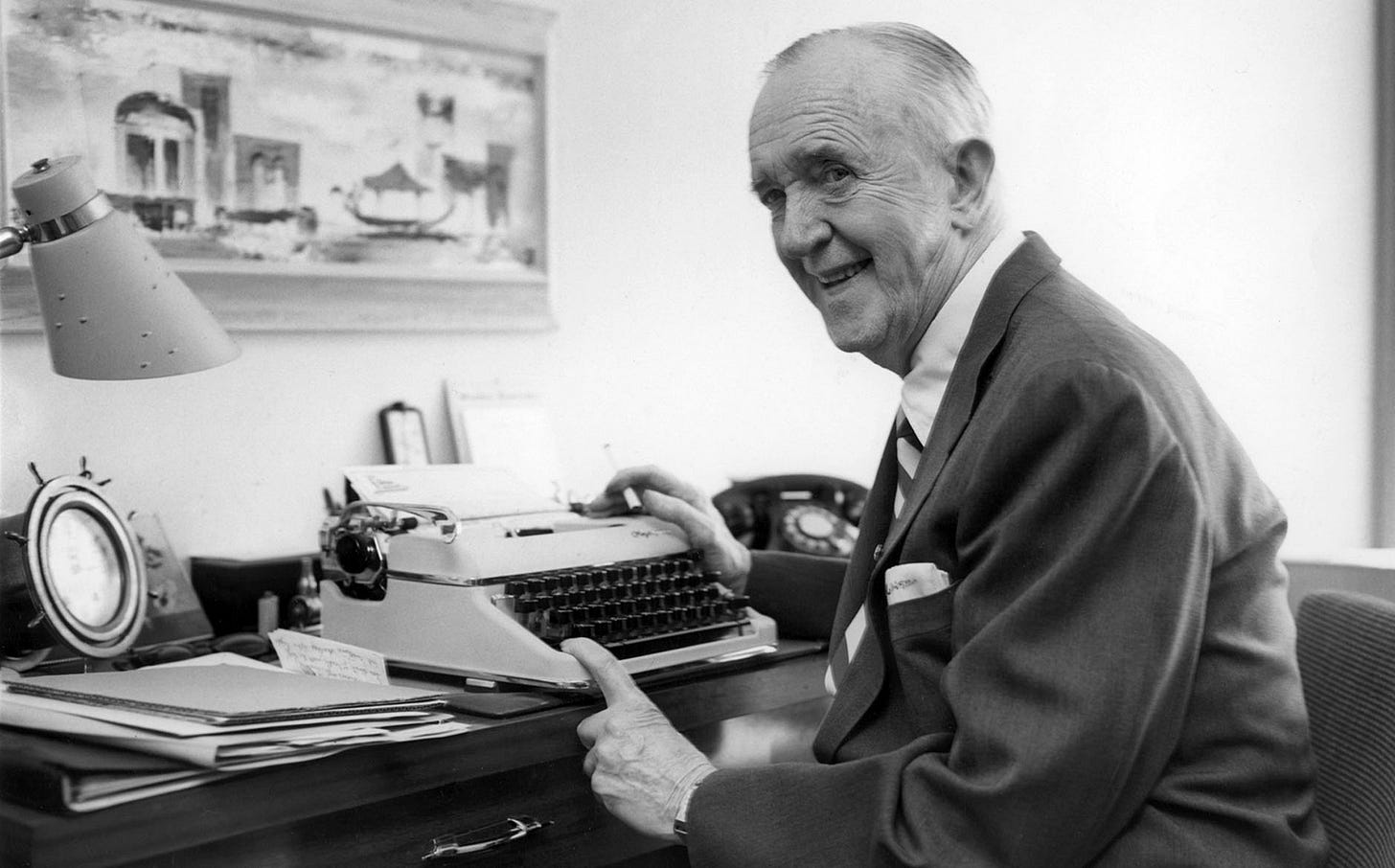

Sad and lonely Stan Laurel

Stan Laurel, as portrayed by two great writers like Osvaldo Soriano and Paco Ignacio Taibo.

- "My father said that cinema will kill comedians," says Stan (Laurel).

- "It will kill comedians without talent," Charlie (Chaplin) replied, without looking at his increasingly distant companion, enchanted by the lights. He feels that the time is coming, that all of North America is a silent audience waiting to see him set foot on the coast. (...) The ship's siren shakes him, makes him open his light eyes that hold more fire than ever, and he notices around him the joy of his companions celebrating their arrival. Stan quickly smiles. He covers his face with his hands because a vague and unpleasant feeling grips his heart and stomach. Through the open fingers surrounding his eyes, he looks at Charlie and feels a love for him like no other, because he knows he is facing a winner.

The barges approach the ship and tow it. The day is bright, and the fog has lifted. Some actors drink Scotch and shout incomprehensibly. They will soon return to London, embrace their wives and children, and recount the adventure of the tour. Stan and Charlie have no return ticket. (...) Charlie has lit a cigarette and waits for his turn on the gangway. He is no longer part of the troupe. A surge of warm blood fills Stan’s veins, and his face comes alive. He guesses that Charlie is betting on success and fame. From a pocket, he takes a handful of shillings and fiercely hurls them into the sea. He is left alone, and if he could see himself, he would feel ashamed.

- "They won't kill me, Dad," he says, and jumps ashore. (Osvaldo Soriano, Triste, Solitario Y Final)

Stan Laurel was a great comic actor. In partnership with Oliver Hardy, he made half the world laugh, creating a new cinematic genre. The image we have of him is the one built through the 107 (106?) films in which he starred: naive and clumsy, silly and awkward. The Italian dubbing gave him a funny English-accented voice that made him even more popular, like an icon of the past known by all.

The son of a theater manager/promoter, Laurel followed in his father’s footsteps from a young age, dedicating his entire life to acting. He left England for the first time in 1910, following Fred Karno's troupe, whose main comic was Charlie Chaplin.

That steamer journey is depicted through the imaginative pen of Osvaldo Soriano, as we read in the introductory passage. Chaplin was heading toward global fame, while Stan began to wander around the United States, trying to find his own comedic path. For the time being, he remained an imitator of Charlie, of whom he was the second in the Karno company.

Marriage with an Australian actress, Mae Dahlberg, who changed his surname from Jefferson to Laurel, was the first of many to come. Short comedies brought him a modicum of success and introduced him to Hal Roach. Then came the breakup with his wife, deemed unsuitable as a co-star by producer Joe Rock.

Here, in a kind of space-time short-circuit, the imagination of another great writer, Paco Ignacio Taibo, weaves into the story, recounting an imaginary Mexican escape by Stan in Four Hands.

On July 19, 1923, around half-past five in the afternoon, the man stepped onto the international bridge separating El Paso (Texas) from Ciudad Juarez (Chihuahua). It was hot. Four wagons carrying barbed wire toward Mexico had filled the air with dust.

The Mexican customs officer, from his post, cast a brief glance at the thin man in gray, advancing towards him with a black bowler hat and a curious leather briefcase. He gave him no importance and returned to the volume of Rubén Darío's poetry, trying to memorize a poem to recite while lying among the pillows of a French prostitute he knew, who adored such things.

The thin, awkward man, walking through swirls of dust, reached the desk of the Mexican customs officer and discreetly placed his briefcase on the counter, as if he wanted to mind no one's business, not even his own. The guard lifted his head, lost among acanthus flowers and colorful-feathered birds, and studied the man with care.

The face seemed familiar. Perhaps someone who often crossed the border? A sales representative? No, he dismissed the idea. Exaggeratedly pale face, protruding ears, a mouth longing for a smile that wouldn't come, small and frightened eyes.

He felt the urge to protect him, maybe to recite poetry together. The thin gringo didn’t even glance at the Mexican official studying him. The customs officer resumed his duties, opened the suitcase: eight bottles of Dutch gin neatly arranged and nothing else. Not even a pair of socks or any underwear.

The damned gringo would get himself drunk to death. Why didn’t he do that in his own land, the fool? But he couldn’t formulate any nationalistic tirade. He decided that the strange American was a fellow sufferer. Another unfortunate one, wrecked by a woman. And he felt a vast, overflowing solidarity grow within him.

He closed the suitcase and drew a white chalk line indicating clearance. The gringo, suitcase in hand, entered Mexican territory without uttering a single word. The customs officer watched him walk away through the dusty streets of Ciudad Juarez, and as he returned to his reading, he remembered why that thin face with big ears was so familiar, and even recalled his name: Stan Laurel, someone he had seen in films shown at the Trinidad cinema—a comic actor.

Stan would settle at the dilapidated Neptuno Hotel in Parral, where he would watch from his window, with the first of the eight bottles of gin, the assassination of Pancho Villa in an ambush by nine men, with two hundred shots fired at his car.

A different Laurel from the one we know: the stories by Taibo and Soriano imagine sides of him unknown to most. Soriano portrays him again, now old, hiring a penniless Philip Marlowe to investigate why his fame vanished.

By then, Oliver Hardy was already dead after a long series of cardiovascular problems that left him bedridden and, after a 70-kilo weight loss, unrecognizable.

Stan confides in Marlowe that he is dying too and wants to know why Hollywood has forgotten him. I think of—and do not dismiss—the comic strip by Andrea Pazienza, Why Goofy Looks Like a Stoner.

In the comic, Goofy is a hippie hanging out in a kind of commune, spending his time in toxic revelry with friends, chased by a cynical and ruthless Mickey who tries to take him away to exploit his comedic talent. The price one pays for success often sees the system exploiting talents to exhaustion.

Hollywood, in a way, sucked the marrow from Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy. Hardy died in utter poverty, and Laurel led a more modest lifestyle in his final years, barely able to pay for his accommodation.

The pair was born by chance when Hardy had a severe fall on set, burning his arm with a pot of boiling water. Laurel, the director, had struggled greatly to get this opportunity and fell into a hysterical fit, thinking the accident would ruin the film. He rushed to the set, throwing a tantrum, pounding the ground while Hardy moaned in pain. Hal Roach, the producer, found the scene irresistibly funny. Thus began the career of the most famous comic duo in cinema history.

Laurel reinvented comic cinema, personally directing (though uncredited) and meticulously crafting the irresistible gags we all know. A revolutionary figure capable of codifying an art form. The world laughed for at least ten years; Stan's formula survived the advent of sound and longer film formats. Then the war drained everyone’s desire to laugh.

They earned little, without royalties for the films they made. Producers forced them to work in settings unworthy of their talent and demanded Stan cease his creative contributions. He was tormented by his turbulent love life, enduring an endless cycle of marriages and divorces, wrong relationships where he often had to endure the invasive behavior of the women beside him. Lack of love.

The delicate, complex figure emerging from Taibo’s and Soriano’s stories seems more in tune with Stan’s life: a kind man, a loyal friend to the exuberant Ollie, driven by an infinite passion for his work. Excessively generous with colleagues and with numerous fans who wrote to him when he was just a famous actor known by no one.

Soriano also recounts the journey to England, where Laurel returned with Hardy for a tour. They traveled through Europe, rediscovering the applause of people who hadn’t forgotten them, but their health prevented them from keeping up with the grueling pace of the tour.

During this journey, forty years after leaving his homeland, Stan finds his father again, to whom he can finally say he is still alive.

Cinema hadn’t killed him because he was a comedian with talent.

Post translated into English using ChatGPT